Seventy years ago, I addressed the pressure

History applies to creativity and society,

Let us say, news more pretentious than

Any description of it, but that pressure

Continue reading “Wallace Stevens Encounters Hyper-Connected World”

YAWB – Yet Another Writing Blog

Just another Poetry site

Seventy years ago, I addressed the pressure

History applies to creativity and society,

Let us say, news more pretentious than

Any description of it, but that pressure

Continue reading “Wallace Stevens Encounters Hyper-Connected World”

As Part of a class in my MFA program titled Literature for Writers, Professor Janet Peery asked for a final project interrogating our semester-long study of our choice of writer. At the beginning of the seminar, I chose Wallace Stevens as a poet I should probably know more about, as my encounters with him have been few and far between.

After attempting several different projects, including a couple of essays, I decided to go a little more playful: bring Stevens into contemporary America and see what happens. The posts included under this category are the results.

Many of the readers who end up at this blog do so by searching Google with the phrase “idealism in poetry” or something similar. While I think the overall contents of the blog offer my thoughts on the topic, I am sure that many of these searchers are looking for research for their undergraduate or high school papers. This post will offer some reflection on the concept in general, but I would like to also point them toward the recently updated “plagiarism note” in the right column. Your teacher/professor will recognize a voice other than yours, and drop text into Google to figure out where it came from. Then you will fail the paper, if not the course. Be forewarned.

Every poet claims that poetry is political – or at least that the act of writing poetry is a political act – no matter what the poem’s contents are. Jane Hirschfield, Richard Hugo, David Orr, Susan Stewart, and Stephen Dunn are just a few of the poets investigated this semester who wrote or intimated this idea. The statement that poetry is political requires a certain understanding of the “political,” meaning an exercise and projection of the voice in the face of the vast ease of being silent. This idea, that saying what needs to be said – whether about a white spider on a sprig of Queen Anne’s Lace, or about the unequal gender treatment in our current society – is a political act opens more than just poetry to political statement, but all fields of art. As a result, the question of which writing is political, and which is not, becomes very important. To hazard one possible boundary, writing which does not offer some access to Truth, or which deliberately obscures Truth (or truth), falls on the far side of the political; these kinds of writing result in either apathetic consumerism, or worse, outright propaganda. Much popular music falls into these categories. The reader (that’s you) may object that even apathetic consumerism or outright propaganda fall somewhere on the political spectrum, and the author (me) may agree. In that case, let us use “political” – in terms of writing and poetry at least – for the positive – seeking awareness and Truth – end of the spectrum, while the previous terms (apathetic and propagandist) can apply to the other, obstructive end. Continue reading “June Jordan and the Political”

This post is inspired by an essay I wrote about June Jordan’s Kissing God Goodbye, in which I address some of these issues by looking at how she manages the problems. That essay will soon appear here (as soon as it’s turned in), but in the meantime, and as a way to clarify my own thinking on the subject, I offer the following thoughts on pitfalls facing political poetry.

“Political” requires some definition, for which I’ll steal my own introductory paragraph:

Every poet claims that poetry is political – or at least that the act of writing poetry is a political act – no matter what the poem’s contents are. Jane Hirschfield, Richard Hugo, David Orr, Susan Stewart, and Stephen Dunn are just a few of the poets investigated this semester who wrote or intimated this idea. The statement that poetry is political requires a certain understanding of the “political,” meaning an exercise and projection of the voice in the face of the vast ease of being silent. This idea, that saying what needs to be said – whether about a white spider on a sprig of Queen Anne’s Lace, or about the unequal gender treatment in our current society – is a political act opens more than just poetry to political statement, but all fields of art. As a result, the question of which writing is political, and which is not, becomes very important. To hazard one possible boundary, writing which does not offer some access to Truth, or which deliberately obscures Truth (or truth), falls on the far side of the political; these kinds of writing result in either apathetic consumerism, or worse, outright propaganda. Much popular music falls into these categories. The reader (that’s you) may object that even apathetic consumerism or outright propaganda fall somewhere on the political spectrum, and the author (me) may agree. In that case, let us use “political” – in terms of writing and poetry at least – for the positive – seeking awareness and Truth – end of the spectrum, while the previous terms (apathetic and propagandist) can apply to the other, obstructive end.

Continue reading “The Pitfalls of Outright Political Poetry”

Richard Hugo continues the sentence in one of the most powerful essays of The Triggering Town by writing, “but it would be honest and I would like it because it wouldn’t be any tougher than the human heart needs to be” (96). “Ci Vediamo” barely resembles other essays in the collection, with very little direct advice, but instead reflects on Hugo’s return to the little Italian town where he was stationed in WWII. Despite not directly conveying advice to writers, Hugo imbues the essay with a well-modulated experience which brings the reader to tears with the author at the end. This control of modulation offers enough to study in itself, though this response is not the appropriate place. Instead, this essay will examine the way “Ci Vediamo” and other essays in Hugo’s collection urge the reader toward an honesty and openness which leads to better poems.

Continue reading ““I Didn’t Know How Good the Poem Would Be” – Hugo and Finding Out”

My peers and professors kept recommending Jane Hirschfield’s Nine Gates: Entering the Mind of Poetry to me, and with this class I found the ideal exploration space for this collection of essays. I read Susan Stewart’s Poetry and the Fate of the Senses previously, which she wrote in a density close to that of black holes, as well as Stephen Dunn’s Best Words, Best Order, written in a more clear diction. Maybe one reason for putting off Hirschfield’s book was the concern that it would approach Stewart’s complexity as opposed to Dunn’s clarity. I do not shy away from complex theory, I enjoy it, but find that along with that complexity comes a requirement for time spent contemplating. Continue reading “The Focus Gate Opens: Reflections on Jane Hirschfield’s “Poetry and the Mind of Concentration””

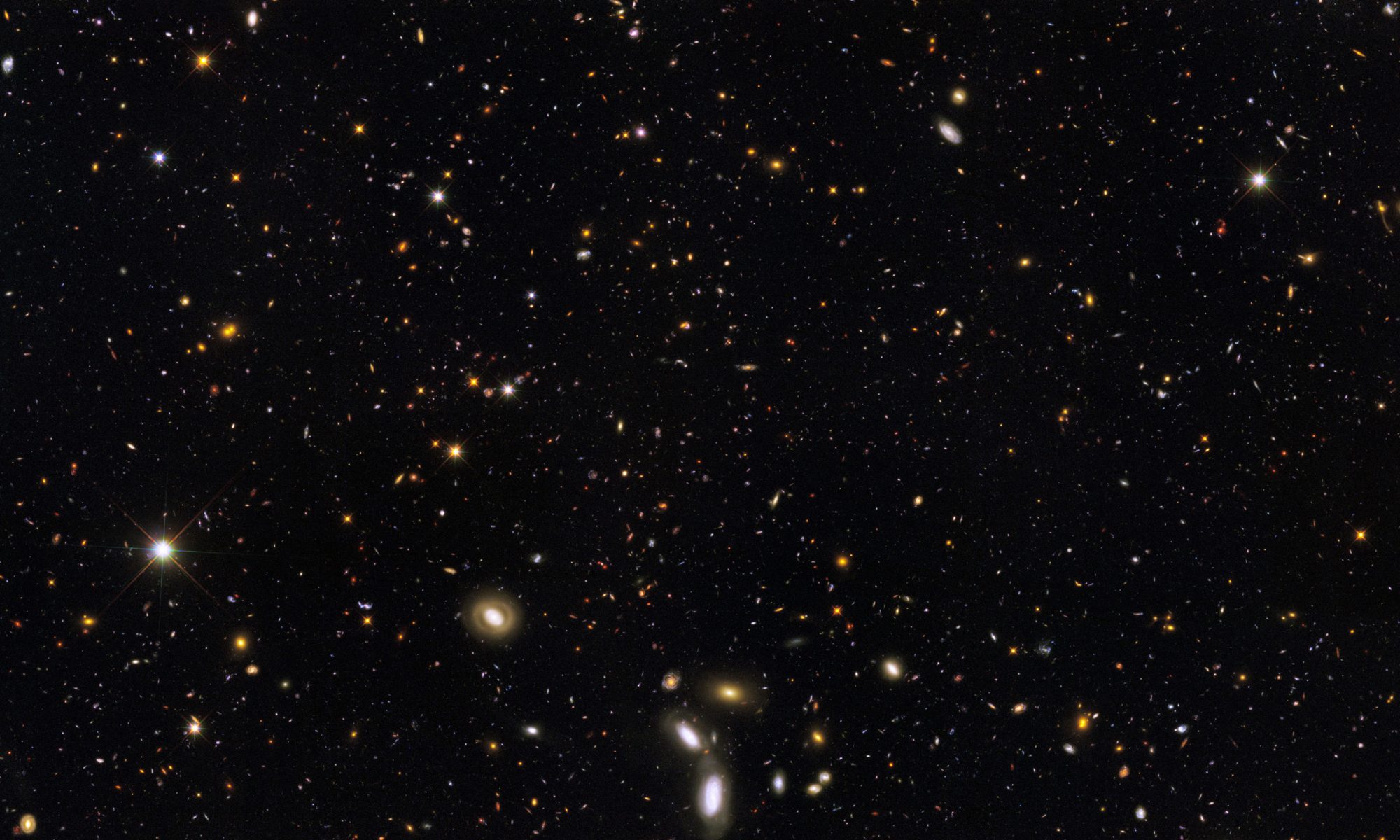

I first ran into Tracy K. Smith’s collection Life on Mars through a National Public Radio interview. It fascinated me that there was a poet writing a collection that seemed in the vein of what I want to produce for my thesis, and I immediately ordered it. As an investigation of the human in the face of grief, it is excellent; as an investigation of humanity’s place in the universe, it is a little bit disappointing. While Smith does interrogate a human understanding of life and death, and the process of coming to terms with dying, the collection is much more centered on that issue than the questions I am interested in. These questions aside, there are a couple of poems which question the human locus within the universe, and it is these poems (“Sci-Fi” and “My God, it’s Full of Stars”) I would like to examine more closely here. “Sci-Fi” polishes up the crystal ball and looks into a future of humanity, while “My God, it’s Full of Stars” investigates the question of life elsewhere in the universe, our relationship to it, and concludes with Nietzsche’s abyss staring right back at us. These two particular poems intrigue me because they remain grounded in a perspective from the human-scale viewpoint; it could reasonably be argued that the group of poems I am pursuing currently lacks this perspective. Continue reading ““So brutal and alive it seemed to comprehend us back.””

This Poem for My Wife

Thanks for reading this, everyone. I’ve taken it down for revision, and because I’m thinking about sending it out after that. I hope you enjoyed!